The last official survey to assess child labour in Vietnam was undertaken in 2018 with the Second National Child Labour Survey. The survey found that more than 1 million children aged between 5-17 were engaged in child labour and it is estimated that over 50 percent of those children were working in the agricultural, forestry, and fishery sectors. But much has changed in the four years since the survey was undertaken, most notably the COVID-19 pandemic. We know now that the pandemic has had a devastating effect on families’ livelihoods, and those living in rural Vietnam who were initially already in poverty have been struck hardest. On this World Day Against Child Labour, the ILO and UNICEF are reminding us that the majority of workers in informal work settings like agriculture are not covered by social protection and are therefore extremely vulnerable to shocks like the pandemic. According to the ILO, before 2020 53.1 per cent of people worldwide – as many as 4.1 billion people – did not enjoy any form of social protection benefit.

How are the combined issues of poverty, lack of social protection and a global pandemic effecting families linked to agriculture supply chains? The following real-life story offers a glimpse into what life looks like for some. Please scroll all the way down to watch a video about his story and links to further reading.

Y.D.A’s story, a young life in child labour

In 2021, The Centre travelled to Dak Lak Province in Vietnam to carry out a child rights impact assessment for a client in their pepper plantations. As part of the assessment, we spoke to a range of people involved in the pepper harvest and visited the plantations first-hand. During this trip we met Y.D.A, an 11-year-old boy from an ethnic minority group who was working on the plantations with his parents and had never been to school. In many ways, Y.D.A. became a symbol of the unknown numbers of children in rural Vietnam who too were out of school due to poverty, working and making “invisible” contributions to an international company’s supply chain.

Reasons for working

Y.D.A.’s parents are seasonal agriculture labourers, who travel from one province to another to work on whichever harvest is ripe for picking. Y.D.A.’s family is extremely poor and as the third child, the parents have never been able to send him to school. They also struggled to find someone to take care of him during harvest season so they would bring him along to help with work. At the time of the assessment, Y.D.A. had already worked on pepper, cashew and coffee plantations.

Working conditions

Y.D.A. worked long hours similar to other adult farmers. He usually started from 7:00 in the morning and finished at about 4:30 in the afternoon with only one hour break in between. He would climb up high ladders to harvest pepper under the scorching sun. His mother was really sad to see her boy work under such conditions but she had no choice.

Initiating a remediation despite lack of cooperation from the brand and supplier

The Centre discussed Y.D.A.’s situation with the involved brand and supplier in the hopes of securing financial resources to develop a tailored remediation programme for him, one that would keep him away from hazardous work and provide him with a long-overdue education. However, the involved stakeholders would not agree to covering the cost for the remediation plan. Neither party felt responsible and there was no system in place for dealing with child labour at the agriculture-level of the supply chain. Had it not been for our child rights risk assessment, Y.D.A.’s case would have never come to light.

The Centre decided to fund Y.D.A.’s remediation using the Child Labour Remediation fund, which consists of unused funds from remediation budgets and is used to fund emergency cases. To date, this fund has helped dozens of children continue their education after their official remediation programme ended, and has been a lifeline to families in extreme poverty during the height of the pandemic.

A tailored remediation programme

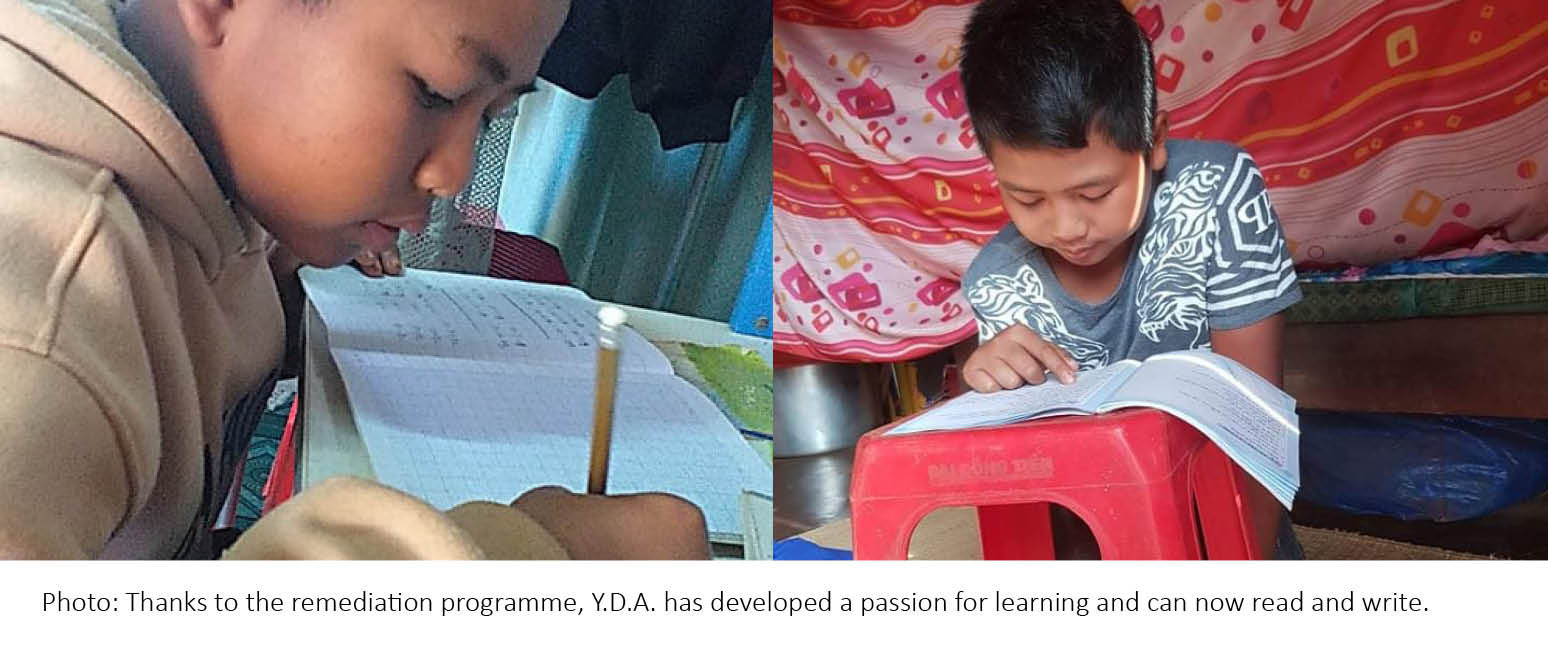

As Y.D.A. was illiterate and had never spent a day in school in his life, it was difficult to gain admission to a regular school. Instead, The Centre found a retired teacher who agreed to homeschool him. Within just one year, Y.D.A. learned Vietnamese reading, writing and simple math equivalent to Grade 1 level of primary school.

“He came to every session and was very attentive. The boy could start to write and read some simple words on his own,” said the teacher a few months into the lessons.

“He was excited and could not wait to start the first day of class. I bought him new clothes to prepare as well,” his mother said. As part of the remediation programme, the boy’s family also receives a monthly living stipend. The living stipend is alleviating their financial woes and allowing the boy to fully focus on his studies.

What does the future hold?

“I really like going to the classes during the week and I want to study more,” Y.D.A told The Centre during one of our regular check-ins.

The target for this year is for the boy to reach Grade 2 level and The Centre is continuing to coordinate with the boy, his family and the tutor to help him achieve his goals. We are also taking into consideration the fact that Y.D.A will soon reach the minimum legal working age (15 years old in Vietnam) and will benefit from a more advanced course such as basic vocational training once he turns 14 years (the minimum age to attend vocational training) so that he will be ready to find a decent job to support his family as per his will.

Although this is the story of just one boy, around the world millions of children are in similar situations. Unlike the manufacturing sector with its formalised Tier 1 factories and direct links to buyers, the true situation of working conditions in agriculture is far more opaque. In many cases, there are no audits to detect child labour cases, and no systems in place to remediate or support the children. But as this story shows, not detecting cases does not mean child labour is not an issue. In Y.D.A.’s case, the only reason his situation came to light is because The Centre happened to conduct a risk assessment there. And the only reason he was given access to remedy is because The Centre happens to have a child labour remediation fund for emergency cases. Fates like Y.D.A.’s should not be in the hands of luck or coincidence.

On this World Day Against Child Labour, we call on all businesses to take responsibility in their lower tiers, and to not overlook the very-real risk of child labour in agriculture. Specifically, we call on businesses to:

Begin by acknowledging child labour risks and the need to face the issue proactively

Assess your business practices including payment structure so that workers in your supply chain earn a living wage

Increase visibility and traceability in your supply chain

Allocate more funds to build robust prevention and remediation mechanisms

Shift resources to support lower tiers

Directly engage with communities, grassroot organisations, and the workers and children themselves to monitor and address child labour cases at all tiers

Talk to The Centre on how we can support you in this endeavour

“I am so happy because my son can study now and he is able to read. I also hope that the companies will pay us better so we can take care of our children better, my son can continue to study and does not need to work for a living,” said Y.D.A.’s mother.

Watch this video about Y.D.A.’s story.

Further Reading on Which Actions Companies can Take to Eradicate Child Labour

Please read our article for World Day Against Child Labour on Business and Human Rights Resource Centre's website for tips on which practical actions businesses can take to accelerate action to tackle child labour and other key human rights risks in supply chains.

2025/12/16

Webinar: Addressing Child Labour in Complex Upstream Supply Chains: Agriculture, Mining and TextilesBy using this website, you agree to our use of cookies. We use cookies to provide you with a great experience and to help our website run effectively.